THE ETHERIO-ATOMIC PHILOSOPHY OF FORCE.

I.—Atoms.

Atoms are the primary and indivisible particles of things. To understand them fully would be almost to understand infinity. In fact we cannot understand the exact nature of the simplest object without apprehending its atomic constitution. We shall not be real philosophers until we can reach far back toward primates and thence onward toward ultimates. We shall be but poor chemists so long as we cannot tell the law of atomic action in any substance whatever, or the basic principles of chemical affinity.

II.—Force.

Force is a leading phenomenon of the universe. Without it, all movements of worlds, all chemical affinities, all wonders of light, color, sound and motion, all attractions and repulsions, all life, human, animal and vegetable, in fact every impulse of thought or affection itself must forever cease. Happy shall we be if we can get even a glimpse of its basic principles, for force and matter include the sum of all things.

III.—The Size of Atoms.

The infinity of smallness in nature is quite as wonderful as the infinity of vastness, and equally beyond all human comprehension or flight of imagination. Persons of large conceptions which lead them far into the grasp of things as they are, are often called visionary by those of smaller conceptions, but the grandest visions and stretches of thought are tame and small compared with the realities of things. Ehrenberg, who investigated the subject of infusoria very extensively by means of the microscope, estimates that an ordinary drop of water, one-twelfth of an inch in diameter, may contain 500 millions of these animalcules, and remarks that "all infusoria, even the smallest monads are organized animal bodies and distinctly provided with at least a mouth and internal nutritive apparatus." As each of these must have some tubing and fluidic circulation it would doubtless be safe to estimate its number of atoms as high as 1000. This would make the number of atoms in the animalcules of a drop 500,000,000,000, besides the countless atoms which compose the water itself. The atmospheric bacteria are still smaller, as other scientists have shown. Thompson, by means of numerous experiments, has established the fact that in transparent bodies the atoms are so small as to require 250,000,000 to 5,000,000,000 to extend one inch, and Gaudin calculates for the smallest particles of matter figures much the same as those of Thompson, making the number of atoms for a large pin's head about 8,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 (8 sextillions) which, if measured off at the rate of a million a second, would take over 250 million years to complete! This taken in connection with the wonderful and beautiful character of each atom becomes one of the most amazing facts in the universe. But even this is doubtless far below the infinitude of nature's smallness, as the finest ethers must have atoms quite transcending in minuteness all measurements, or comprehension of the human mind.

IV. The Form of Atoms.

1. In the first place atoms are evidently not spherical, as some have supposed, as they would not combine thus properly, and would not so well carry out the law of positive and negative conditions without which all life and action must cease. This will be shown hereafter.

2. The lines of atomic force, are doubtless not in circles, this being contrary to the general untrammeled movements of nature, as the pathway of missiles, cataracts and planets is in the sections of a cone.

3. Some philosophers, believing with Bishop Berkeley that the whole universe is spiritual in its nature, conclude that atoms must be spiritual, or mere circular forces which in some way overlap, combine and crystallize into the forms which we call matter. Others, believing with Hume and Buchner, that matter is the beginning and end of all things, of course consider the atoms merely material.

4. We have seen the folly of these extreme positions in the last chapter, and having learned that everything possesses a finer positive principle, and a coarser negative principle, we may confidently presume that each atom has its imperishable framework, with the definiteness of position which is supposed to belong to materiality, and yet an inconceivable exquisiteness, elasticity and spirit-like freedom and flow of force.

5. What, then, are the lines of atomic force? Let us see if we cannot find a suggestion by noticing what are nature's great lines of force. Our sun, as we have seen, is moving around some greater sun. This greater sun is also moving onward, probably around some still greater centre, and carrying our sun with it. Our sun, under this double motion, then, must describe a vast spiral through the heavens. Again, our earth moves around the sun, and at the same time is carried by the sun around its centre, making a smaller spiral somewhat less than 200,000,000 miles in diameter through the heavens. Then, finally, the moon makes its baby spiral of about half a million miles in diameter around our earth. Thus we have first the great solar spiral, then the telluric spiral around the solar, then the lunar spiral around the telluric, three distinct gradations on nature's favorite trinal plan.

6. Let us suppose now that atoms are in ellipsoids, or rather in the modifications of this form in the ovoid, which, as we have seen, in Chapter First, is the most easy and beautiful of simple enclosed forms. "What nature does generally is beautiful," says Ruskin, and atoms being the most general of all things, we cannot suppose them for a moment to be anything but beautiful. So far, it may be said, we are building on mere supposition, but it will be shown more and more as we advance that there is a ne-essity for this form. One thing in proof of this is the fact that atoms will combine and polarize better by having a smaller end, while, as will be shown, the law of positive and negative action forces one end to be smaller than the other.

7. But where must the lines offeree run, over or through this atom, or both? Let us see. We have ascertained in Chapter First that the spiral, itself the most beautiful of continuous forms, is the great leading law of motion in nature. Let us presume, then, that the spiral direction rules in atoms as well as in worlds, especially as, according to the great unity of law, we must judge the unknown by the known. In fact the spiral is a necessity if we are to get any continuous lines around the atom and have it progress regularly so as to cover its whole form and then convey its force over to the next atom. So far, then, we have the external atom clad with spiral lines of force, or rather, a spiral framework, and tube-work through which, and over which, this force must vibrate and flow.

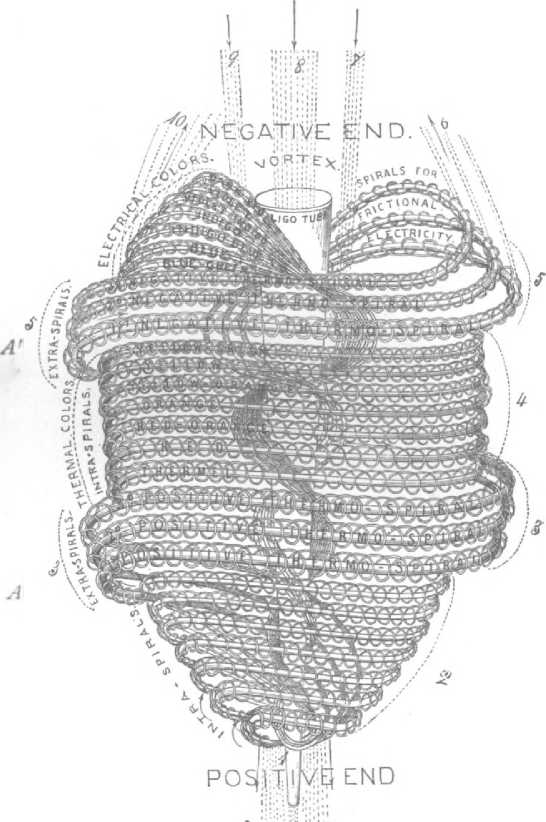

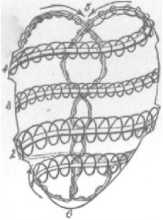

| Fi:132, Outline of an Atom. |

8. Fig 132 gives a simple representation of this atomic coil or helix, commencing below and moving round and round the atom from left to right, until the other end at 4 is reached. Let us first consider the effect of this external spiral movement which sweeps around with inconceivable rapidity. It is a well known fact in electricity and magnetism that when the conducting wire is wound in a spiral coil, its heat producing power is greatly increased. Another fact which harmonizes with the same thing is that the greater the heat, the greater the expansion, other things being equal, and here we can see just how it is that heat produces expansion, for the more powerful the sweep of forces around the atom, the more it will increase the outward or centrifugal force. One leading principle for the development of heat is that there shall be obstacles to overcome, or a laboring style of movement, and this explains why this ever twisting movement of the spiral is the distinctive one for heat.

9. Let us see how the line of force would work as it vibrates this exquisite wire-work which is untold millions of times finer and more elastic than any wires of copper or steel. Commencing at 1 it gets under greater and greater momentum until it swells the atom out to its greatest size at the middle or a little beyond, and then becoming gradually spent, the coil grows smaller at 3, and reaching the larger negative end at 4, the

7

heat-force of the other end is felt through the axial portion and draws it in through the middle of the atom to the smaller end, where the circuit is recommenced.

10. This current of force through the centre of the atom, acting like any fluid under the same circumstances, becomes a vortex and tends to draw the other portions inward by its suction. This, without doubt, is the principle of cold as is proved by the following facts:—1st, it is contracting in its nature, and cold is contracting; 2dly, it moves in the opposite direction from heat which shows why the needle of the galvanometer, connected with the thermo-electric pile, moves in one direction for cold and another for heat, as Tyndall and others have often noticed; 3dly, the swifter the movement of the forces, the more narrow, piercing and contracting is the stream, and this harmonizes with the known effects of cold, which is piercing and contracting in proportion as it becomes intense; 4thly, as a great principle of equilibrium in nature, it is necessary that one part of atomic force should develop cold in a way to balance the heat action, and 5thly, the flow of forces could not be kept up at all were it not for the law of cold, to intensify the law of heat, just as the heat intensifies the law of cold, as will be seen more clearly hereafter.

11. But in order to work properly, there must be a more intense heat-action at the smaller end in order to draw in the forces that reach the negative larger end from the outside. How can this be effected? Is not the heat the greatest at the larger part of the atom where the spiral is most expansive and intense in its action? Yes, so far as this spiral is concerned, but there are other processes by which this may be caused. As nature ever deals with gradations of refinement, and as in the solar system we see three grades of spirals with the smallest encircling the next larger, and this larger encircling one still larger, so we may presume that the atomic system continues the analogy and has different grades of spirals also. The fact also that there are known to be so many grades of force, would argue in favor of different grades of fineness in the atomic coils.

12. Fig 133, presents the main spiral which passes around the atom, then a sub-spiral which encircles the main spiral. This may be called the first spirilla or little spiral. Judging by nature's usual law of trinal gradations there is probably a still finer spirilla that encircles this first one which may be called the second spirilla, and another which encircles the second one, more minute still, and properly constituting the third spirilla. The different grades of forces that flow along this spiral and these spirillae must pass around the atom in the same direction, just as the sun, planets and moon all move along through space in the same direction, namely from west to east.

| Fig 133. Piece of Atomic Spiral with 1st 2nd and 3rd Spirillas. |

V. The Heat End of Atoms.

1. From the foregoing, then, we may now begin to see how one end of the atom will naturally become warmer than the other end, although the spiral itself may be less expanded with heat action. The first spirilla, being much more elastic than the spiral, must spring into its full heat action and power near the positive end, say at 1, and the 2d and 3d spirillae; still sooner. These become more exhausted and feeble at 2, near the negative end, after having imparted their force to the spiral. That is, the 3d spirilla, being most active, quickens the 2d, the 2d quickens the 1st, and the 1st quickens the spiral itself.

2. Another method of intensifying the heat of the positive end is to have the spiral lines nearer together there than at the negative end, as in fig 132, a method which nature probably adopts, as it is absolutely necessary to have the positive and negative distinctions well emphasized to attain the highest power. Does the reader see this important point? By having the external positive end hot it draws all the more powerfully upon the axial current within and thus intensifies the cold, and then again the swifter the cold-producing currents the more will they react and draw upon the heat-currents on the external atom, other things being equal. Thus beautifully does nature develop her intensity of life and action, by causing one extreme to vitalize and balance the other. Action on any other plan would be ruin, or rather action without positive and negative forces would be impossible, and so universal death would ensue.

VI. Nature of Atomic Spirals.

1. As in animal life there are millions of tubes, such as lymphatics, lacteals, capillaries, veins, arteries, nerves, etc., and as in all vegetable growth there are countless tubular ducts to convey the life fluids, so we may conclude that an atom with its intensity of life-like action has its spirals and spirillce in the form of tubes, within which are still finer ethereal juices which constitute its most interior life-force. That these spirals are amazingly elastic is shown by the fact that they expand to a size 2000 times greater in ordinary atmosphere than in water, while in the upper atmosphere, and especially in the ether beyond, they must be far more expanded still.

2. The most common arrangement of atomic spirals is doubtless two-fold, as will be shown hereafter, consisting, 1st, of

coarser and more external groups of spirals such as 2 and 4 in fig. 134, which may be termed extra spirals, and 2dly, finer spirals set farther in, such as 1 and 3, which may be called intra spirals.

The need and existence of these will become more and more apparent as we advance, besides fulfilling nature's analogies. Instead of there being but one intra-spiral at 1 and 3, or but one Faiid intfsXspi^raU extra-spiral as at 2 and 4, there is probably a gradation of several of them placed side by side in all the more complex grades of atoms, say from 3 to 7 in each place. The need of seven spirals in all transparent atoms, in other words in atoms of substances which transmit all the colors as in transparent bodies, will be evident. The positive intra-spirals are grouped at 1, the positive extra-spirals at 2, the negative intra-spirals at 3, the negative-extra spirals at 4, the atomic vortex into which the spirals all sweep with vortical whirl is at 5, the torrent at which the forces become most pointed and swift is at 6, and the axis or axial current from 5 to 6. The curves caused by the vibration of spirals are not shown in the cut, nor are any but the first of the spirillae given and shown as they must be in nature, and there are doubtless points of connection between spirals, spirillae and all other parts of the atom which make it a complete unity.

VII. General Features of Atoms.

1. Years of investigation of what the general form and constitution of atoms must be to harmonize with and furnish a key to the facts discovered by the scientific world, aided by many more years of inquiry into the fundamental principles of nature, have led me to a very positive conclusion that fig. 135 is the general outline of an ordinary atom, especially of one by means of which all the colors can be made manifest. The hundreds of points to prove it correct cannot be given here, but they will appear more and more all through this work in the mysteries which are cleared up thereby, especially in Chapter V. as well as in this chapter. Although the modification of tints, hues and other forces which are manifested through atoms is almost infinite from the fact that atoms of the same substance must vary within certain limits in the size of their spirillae of the same kind, yet facts seem to indicate seven intra-spirals (4) on the outside of atoms for the warm or thermal colors, and which are properly the thermo-lumino group, whereas the same spirals form the principle of the electrical colors while passing through the axis of atoms. These are all named and located in fig. 135, commencing with the largest spirilla for the hot invisible solar rays called thermel, after which is the slightly smaller spirilla for red, another for red-orange, etc. Passing around the atom and becoming smaller and finer, the same spirillae form the channels for the electrical colors by passing into the vortex and through the axis, thermel being converted into blue-green, red into blue, red-orange into indigo-blue, orange into indigo, yellow-orange into violet-indigo, yellow into violet, and yellow-green into dark violet. The group of thermospirals at 3, 3, are called positive, because the spirillae that surround them are larger and the heat greater than the portion of the same group at 5, 5, which are therefore called negative thermospirals. The group 2, embraces the positive color-spirals, but as they are concealed by gliding into the contiguous atoms, it is only the same group at 4 that are visible as thermo-color spirals, or at the vortex above as electro-color spirals. 9 and 10 represent minute streams of ether, which are simply combinations of much finer atoms, that flow from the thermo spirillae and the thermo-lumino spirillae into the same grades of spirillae in the atom above; 7 and 9 are axial ethers which flow from the atom

| Fig. 135. T he general Form of an Atom, including the spirals and 1st Spirilla, together with influx and efflux ethers, represented by dots, which pass through these spirill®. The 2d and 3d spirilla with their stil] finer ethers are not shown. |

i

above into the axial spirillae of this atom; 8 represents ethers which flow through the ligo tube, and these and other ethers are represented as passing on through their appropriate channels until they emerge at the torrent end. These ethers sweep through the atom and quicken its spiral wheel-work into new life, just as the winds move a wind-mill, or Atoms joined, the waters a water-wheel, while the atom itself, armed as it is with its vortical spring-work, must have a great reactive suction which draws on these ethereal winds.9

2. Why are ethers drawn from spirillae of one atom to the same kind of spirillae in a contiguous atom, and why does a certain grade of ether exactly harmomize with, and seek out, a certain size of spirilla? For the same reason that a tuning fork or the cord of a piano will be set into vibration by a tone made in its own key. In the case of a piano, a cord vibrates to tones of its own pitch, or in other words, to tones whose waves synchronize with its own vibrations. Let us apply this principle to atoms. The vibratory action of the red spirilla throws the current of ether which passes through it into the eddy-like whirl which just harmonizes in size and form to the red spirilla of the next atom above it with which it comes in contact, and which must necessarily draw it on. This second atom passes it on to the red spirilla of the third, the third to that of the fourth, and so on through millions of miles, so long as there is a spirilla of the right grade to conduct it onward. The same process applies to the orange, or yellow, or any other spiral, and, constituting as it does a fundamental principle of chemical action, the reader should note this point well. The same principle applies to the axial spirals whose lines of force, reaching the positive end at 1, make a sudden dart to the outside and thus in part jolt their contents into the answering spirals of the next atom, the blue ethers of this plunging into the blue spirilla of the next, the violet ethers of this into the violet spirilla of the next, and so on.

3. The ethers are efflux as they flow out of one atom or series of atoms, and influx as they flow into an atom or series of atoms. Thus 9 and 7 are influx, and 6 and 10 efflux ethers. The ethers at the torrent end are powerfully efflux, and have momentum not only from the projectile force of this atom, but from the suctional force of the next, into whose vortex this atom is inserted.

4. It should be noticed that the same spirillae which wind around the outside of atoms on the expansive law of thermism, pass on through the axis on the contracting law of cold, and after becoming the most contracted and intense at the positive end of the atom, suddenly plunge to the outside and again become thermal. Thus the very intensity of the interior cold forces may develop intensity of heat, and we at once see why it is that an object which is so cold as to be 60° F. below zero is said to have an effect similar to that of red hot iron.

5. The First Positive Thermo-Spiral at A projects beyond the intra-spirals below and forms a regulating barrier to determine just how far this atom shall be inserted into the vortex of the next atom: in other words, this atom becomes sheathed in the next as far as A, while the atom above becomes encased in this precisely the same distance, and so on, which accounts for the great regularity of form in crystallizations, etc. In chemical affinity, as I shall show hereafter, the atom glides into a wide mouthed atom up to its shoulders at A' where the second circuit of these same thermo-spirals is seen. By this means the color-spirals are hidden in the encasing atom, and this explains some mysteries of color change which puzzle the chemist, and which will be explained in Chapter V.

6. The Ligo is supposed to exist only in solids, such as rocks, metals, fibrous substances, etc., in which it forms the leading element of cohesion and hardness, while in liquids, gases and ethers it is wanting, which accounts for their flowing qualities. This tube probably has spiral convolutions with openings in the sides something like those Chimney pieces, the object of which is to cause a draft.

7. The seven thermo-lumino spirals which become the elec-tro-lumino spirals on reaching the vortex and axial portion of the atom, naturally grow somewhat smaller, from the smaller space in which they move, and receive a finer grade of ethers from the axis of the atom above at 9 and 7 than those which course through them in their thermal portions on the outside. As they progress through the axis they become narrower, more nearly straight and consequently more keenly electrical until they reach the torrent end. The reason the dark violet is the coldest of all the colors is, because from its position it must circulate with a more narrow and interior course through the axis, as being the highest (See fig. 135), it reaches the vortex and enters before the others, next to which comes the violet, then the violet-indigo, the indigo, the indigo-blue, the blue, and warmest and least electrical of all in the electrical group, the blue-green. My reasons for calling these the electrical group of colors will be fully shown in XXIX of this chapter. All axial forces move on the law of electricity of some kind, while the coarser grades ofelectri-ity impart the ruder sensations of cold, which are so distressing. The finest grades of electricity, while producing the phenomena of cold, such as contraction, do not impart the chilling sensations of cold at all, to most persons. To compose all the colors which constitute white light, both the electrical and thermal colors must be combined and carried along side by side through conversely polarized lines of atmosphere, or other media, through which they are conveyed.

8. The axial spirillae doubtless fill up the whole interior of their atoms from their elasticity, which fact the artist has not quite expressed.

VIII. The Thermo Spirals.

So useful, as we have seen, in regulating the joining of atoms according to absolute system, have other important qualities. They are important factors of heat or thermism in its ordinary coarser grade, and when moving axially constitute the principle of frictional electricity (See XXV). These being extra-spirals, and consequently the most external of all, it is easy to see why friction or pressure begets heat as well as electricity. It is easy to see, too, why frictional electricity moves especially over the surface of bodies as these spirals are so projecting as to strike very freely against all surrounding atoms, consequently their movements are smothered before they reach any considerable depth below the surface. These extra spirals would naturally emerge from the axis of atoms on a side opposite to that from which the intra-spirals emerge, to maintain an equilibrium of forces, and would also pass into the vortex on the opposite side.

IX.—Ethereal Forces.

1. We have now seen that an atom is a wonderful little machine with wheels within wheels, a miniature world through which are manifested the principles of all power both on the earth beneath and in the heavens above. But how is this machine made to run? How do these atomic springs keep up their ceaseless motions, their amazing vibrations, millions of millions of which take place in a second of time, as for instance in light? Has such a thing ever been heard of as a spring that will vibrate forever of its own accord? Has not science determined that perpetual motion in mechanics is impossible? We have seen in the last chapter that in all the known mechanics of man or nature, force is never propagated excepting through fluidic action of some kind. As the wind-mill must have its wind to keep up motion, so must the atom have its flow of ethers to keep its wheels in operation, and form different sized eddies of force. Democritus speaks of "minute atoms in swift motion which by their smallness and rapidity were able to permeate the hardest bodies." In this idea he almost reached the very key of force, showing that he had an idea of ethereal fluids without which no correct conception of nature's dynamics can ever be acquired.

2. But here it may be asked, what keeps the ethers in perpetual motion, for, like the more static atoms through which they move, even they must be vitalized or they will cease. While the spiral forms of the atom, when once in motion, attract the ethers with a fine suction, and while the arrangement of positive and negative portions of the atoms gives still further vitality, making it almost self-acting, still there is the edict of mathematic-cal science which says that perpetual motion in mechanics is impossible. And yet nature and life are in everlasting motion and not an atom of the universe is at rest. How shall we get out of this dilemma? Let us dwell a moment on this point.

X. The Primate of Force.

We have seen that the finer and more subtile a substance becomes, other things being equal, the more potent is its character (Chap. First, XV.), and the more nearly does it seemingly approach self-action. We see also that the merely material universe has no power in itself of perpetual movement—that protoplasm, for instance, which some physicists proclaim as the starting point of all life, must be entirely powerless without some higher and finer principle beyond it: whence, then, is the power that animates all being? If matter alone proves thus insufficient for this continuity of life, are we not driven irresistibly to the conclusion that what we call spirit, must be a necessary factor? In fact is there an example that can be produced in the whole realm of being, in which continuous and self action exists excepting when some principle of spiritual force is combined with material conditions? To reach the primate of power, then, we seem compelled to mount the ladder of fine forces to those which are still finer, until we arrive at conditions so exquisite as to be able to receive directly the impress of Infinite Spirit. But Spirit itself, if we are to judge by all analogies, must flow out and permeate all atoms and beings on a diviner plan, though in harmony with the fluidic process.

XI. Different Grades of Ether.

1.1 have been convinced beyond all doubt by numerous facts, that there are many different grades and styles of ether, and that long before I saw the suggestion of Grove. I will simply notice two or three of these facts in proof here, as the reader will see the necessity of these grades more and more as we proceed. Scientific men generally admit that there is one ether as a medium for communicating waves of light, etc. This of course is immensely elastic and has sometimes been called the Cosmic Ether which is a very proper name, as it constitutes an exquisite atomic bridge-work between the starry worlds over which pass and repass the fine solar and stellar forces of all kinds, such as the different grades of light, electricity, heat, gravitation, etc. The law of atomic arrangement in this cosmic ether will be shown hereafter. In speaking of these ethers and some other subjects, I must in some cases give simply the results of my investigations, reserving the fuller proofs for another part of this work or for a future treatise.

2. The fact that scientific men in general have not ascertained that there is more than one ether just as there is more than one grade of gases or liquids, shows how completely they have ignored the finer and mightier forces, and confined their investigations to the cruder elements principally. In 1773, La Place demonstrated that gravitation acts at least fifty million times as swiftly as light. Can anybody suppose that such a movement of force comes from waves of the same ether, without some finer element being involved? What would be thought of a person who would assert that waves of air in some cases move 1100 feet in a second, as in the production of sound, and in other cases millions of times as rapidly? But nobody will be so absurd in reasoning about visible and tangible matters, and they should use equal judgment in reasoning about the invisible. The analogies of all nature and the necessity of different grades of fluidic elements to express the different grades of force, constitute abundant proof of the plurality of ethers, as will be seen hereafter.

3. In giving the different grades of ethers, those which are generally in motion gliding through larger atoms will be represented by terms ending in o, but those which are more commonly stationary, or nearly so, like the water of a lake, or a quiet atmosphere, will be signified by terms ending in ic. The former are more fluidic, the latter more nearly static. Static ethers are of course sometimes capable of becoming fluidic, just as water may at times flow in streams, or the air be swept into currents, but I speak of their general character, which is to form a bridge-work of channels through which the fluid ethers may pass, just as polarized lines of atmosphere form channels for the solar ethers in the processes of light. But these very solar ethers, even while in full flight through space, may form the bridge-work of incomparably swifter and more subtile ethers, such, for instance, as those which cause the attraction of gravitation, and thus, for the time being, become relatively static though not absolutely so. My investigations have led me to adopt the following as constituting the leading divisions of ethers, progressing, for the most part, towards superior fineness as we advance.

I give them names mainly from the spirals in connection with which they move.

4. The Thermo Ethers flow through the thermo spirilla* and in connection with these, which as we have seen are the most external of all, constitute the ordinary coarser grades of heat. These ethers are too coarse to become visible in the way of colors, but when the heat action is very intense, as for instance in heated iron, the intra spirals become roused into action and manifest first the red light, then the orange and yellow light, then white light, when the iron is called white hot.

5. Electro Ether is the element of frictional electricity used in connection with these same thermo spirals, only on the axial portion. These spirals being the highest and most external while on the outside of atoms, must necessarily enter the vortex first and become the most interior and direct while in the axial portion, hence the swiftness and intensity of its ethers which are transmitted by the shortest pathway, and hence, also, the fact that they are more thoroughly electrical than the other elements of electricity (See XXV.). On the supposition that there are three grades of thermo and electro spirals, there must be three grades of thermo ether and three of electro ether.

6. Thermo Lumino Ether is used in the intra spirillae which form the thermal colors, or in other words with the thermo lumino spirillae. The different grades may be designated the thermel ether, red ether, orange ether, etc. There seem to be two distinct grades of ether for each color, and a very important principle being involved here, a few words of explanation will be necessary. The reader should remember that the seven tubes which pass around the atom constitute the thermal color-spirals, while the still finer tubes that wind around these spirals themselves, are the first spirillae which form channels for the color ethers. Now suppose a red color ether should be thrown upon a red spirilla from the outside, what would be the effect? The finer atoms of such ether would be small enough to penetrate between the tubes of the spirilla and become a part of the interior current, while the coarser atoms, being too large to pass inside, would strike the tubes and bound off. This would constitute a reflected red as in a red building, while the other would constitute a transmitted red as in red glass. If this is true the interior transmitted color should be more exquisite than the ordinary reflected colors, which in fact is remarkably the case, as the colors of a prism or of colored glass are so much more beautiful than those of the ordinary reflected colors seen in paints or dyes, that a young person viewing them for the first time is apt to make an exclamation of delight. The diamond is a good illustration of exquisitely fine transmitted ethers which are shown by its refractive power. That all substances have different grades of fineness is shown in Chapter Fourth, VII., 1—5. These grades can be called transmitted red, reflected red, transmitted orange, reflected orange, etc.

7. Electro Luinino Ether is of course that which is connected with the spirillae of the electric colors, and may be called the blue-green ether, the blue ether, the indigo-blue ether, and so on with the other four colors. These, too, have the fine transmitted grade of ethers and the coarser reflected grade, the latter of which must bound back from the spirillae just within the vortex. The color ethers (or in other words light), move 186,000 miles a second, or about two-thirds as rapidly as frictional electricity, as measured by Wheatstone. It should be remembered that the color-ethers grow finer as they progress through thermel, red, red-orange, orange, etc., up to dark violet and really far beyond that, although they become invisible to the ordinary eye.

8. So far we have the principal ethers which flow through a transparent substance, like glass, including the thermo ethers which flow through the extra spirals, and the electro ethers which flow through the axial portion of the same; also the lumino ethers, both thermal and electric, which flow through the intra spirals and their axial portions. There must be still finer ethers in connection with the second and third spirillae of these same substances, but these will be understood better hereafter. But are there no other forces in nature excepting those thus far named, including light, reflected and transmitted, ordinary heat as manifested by the thermo spirals and spirillae, and ordinary cold and frictional electricity, as manifested by their axial spirals and spirillae? Yes, for there are different grades of electricity, such as the galvanic and magnetic among the more positive styles, and weaker negative grades of electricity, and other still finer forces which will be explained hereafter.

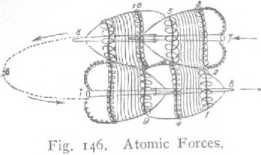

9. We may now descend to a somewhat coarser grade of ethers which sweep through atoms of somewhat coarser character than those that are used for the transmission of light. Iron, and perhaps a majority of opaque substances, belong more or less to this grade. Farther on in this chapter (XXXIII), facts will be adduced to show that the atoms of these substances also have their seven intra spirals in which the ethers are a little too coarse to appear as light, as well as the usual thermo spirals, through which the ethers flow as a somewhat coarser grade of caloric than that of the other atoms. The intra spirals, when they reach the axis of these atoms, have ethers which correspond to those for blue-green, blue, indigo-blue, indigo, violet-indigo, violet and dark violet of the lumen-ous atoms, only, as I have said, somewhat too coarse to produce the effect of color on the retina of the eye. What effect do they produce, then? That of electricity of course, as they flow axially. But what kinds of electricity? We may divide them into three grades, namely, Chemico electricity, Galvano electricity, and Magneto electricity, or the chemico, galvano and magneto ethers in connection with their axial prince-pies.

10. Chemico Ether is a lower grade of chemical force, presumed to flow through the axial spirilla corresponding to the blue-green in the color atoms and perhaps the coarser grade of blue, and constituting the feeblest style of electricity as it is more external than the other axial spirillae. It is doubtless an element of negative electricity, and is quickened into decided action by sulphuric acid coming into contact with zinc, etc. See XXVI.

11. Galvano Ether, the element of galvanic electricity, seems to correspond with the ether for blue, indigo-blue, and probably indigo. It is finer and more powerful than the chemico grade. See XXVII and XXXIV.

12. Magneto Ether, used in Magnetic electricity and Magnetism. Its spirillae correspond to those for violet-indigo, violet and dark violet, as shown by spectrum analysis. This, in connection with some galvano ether, constitutes the positive or north-pole currents of the magnet, while chemico ether is used in the feebler currents of the south pole in connection with thermism.

See Chromo-dynamics; also Plate III., in which the odic colors are a fair test of the potencies of the magnet. Iron, the great leading metal of magnetism, when intensely heated for spectroscopic analysis, has the violet-indigo the strongest of its electrical colors, also the violet, indigo, blue, and blue-green large, which last is the element of Chemical electricity. (Chap. Fifth, XIII).

13. Odylo-Ether, the basic fluid of odic light and force as discovered by Baron Reichenbach, and a grade higher than the ethers of ordinary light. It flows through the 2d spirillae of the intra spirals just as ordinary light does through the first spirillae of the same: also through the first spirillae of odic atmosphere just as light does through the same spirillae of common atmosphere. (See Chap. Ninth.)

14. Psycho Ether, used in connection with mental action (Chap. Tenth), twice as fine as Odylo ether, four times as fine as light, as will be shown. It can pass through the 3d spirillae of intra spirals of ordinary atmosphere, also through the 1st spirillae of the psychic atmosphere, which form all analogies we must suppose to exist.

15. Gravito Ether, the central element of gravitation, inconceivably fine and swift. The reader may already see from the foregoing description of atoms, something of how its attractive processes are carried on between all bodies, all atoms of which exert their suctional forces in all directions so far as this fine ether is concerned. At some future time I shall attempt to explain the processes by which this is done, and by which some atoms become heavy and others light.

16. Cosmic Ether. I will mention briefly some static ethers which are signified by names ending in ic, as I have before said. Cosmic ether, from Cosmos, the world, is the great world-connecting ether of space, whose atoms, polarized by the light of suns and stars, become crystal railways over which light and various other forces pass. In Chapter Fourth, VIII, I have given a number of facts in proof that this cosmic ether is simply a continuation of the finer elements of the atmosphere of the earth and other orbs in the shape of an exquisite grade of hydrogen as its leading element.

17. Odylic Ether is the finer atmosphere within the coarser, through which the odylo ether or odic force finds its most natural pathway. For description see Chapter Ninth, III, 2.

18. Psychic Ether, the atmosphere still finer than the foregoing, through which psycho ether with the psychic lights and colors makes its pathway. It is the same to psycho ether that the atmosphere is to light. (See Chap. Tenth).

19. Miscellaneous Ethers. There are ethers probably still coarser, and of course still finer than any of the foregoing. There is probably a very slow Animo ether which constitutes a vitalizing principle of animal life and the coarser grade of nerve-force. According to experiments made by Helmholtz and Baxt, the mean rapidity of the motor nerve force is 254 feet per second. As we have already seen, the lines of all spirals and spirillae must be tubes if we are to judge by analogies. When I say the line of a spiral, I do not mean the line that passes around the spiral, for this would be the 1st spirilla, but the spiral itself. Within the spiral tube would naturally be polarized lines of minute atoms forming a static ether which may be called Spiric, while in the spirillae tubes the same kind of still smaller atoms may be called Spirillic. These must serve a great purpose, for as they wind around in tortuous lines and are swept by the ethereal forces into countless vibrations, these internal ethers must be chafed with intense frictions which would immediately render the whole tubes alive with heat and quicken the action of the whole atom with all its grades of ether. These spiric and spirillic ethers would also be quickened and held together by exquisitely fine fluid ethers which move in endless circuits through them, and which should properly be called Spiro-Ether and Spirillo Ether. The Ligo Ether, which sweeps through the ligo and drives the atoms together into a close cohesion, must be a cold and swift current on the general plan of electricity. In order to the greatest harmony, the ethers that pass through the channel (not the tube), of the third spirillae, must be twice as fine as those of a 2d spirilla, and those of a 2d, twice as fine as those of a 1st, and the size of these channels themselves, as well as the size of the tubes that form the channels, must vary accordingly. This makes every alternate wave of force harmonize, just as is done in tones which are an octave apart. This same kind of harmony is carried out in male and female voices which average

8

just an octave apart. The reader will understand this the better by studying the laws of undulatory harmony and discord, and by remembering that nature ever works according to the most perfect system. Let not the reader consider the foregoing nomenclature and division of ethers quite imaginary, as he will be finding facts in corroboration all through this work, and still other facts in a future work of the author.

XII. Ethers have Weight,

Otherwise they could not have momentum. It is common to call electricity, magnetism, light, heat, etc., imponderable, because human instruments are not delicate enough to weigh them. Prof. Crookes, however, has succeeded in measuring the momentum of light by means of his wonderful little instrument called the radiometer. By its means he has estimated the propulsive power of sunlight for the whole earth at 3000 millions of tons! His instrument has given the dynamic theorists much trouble. The light of a candle he has found to weigh .001728 or nearly a 900th part of a grain. The amazing forces used in chemical affinity, such as chemico-ether, the luminous ethers, electro-ether, etc., as will be shown hereafter, sweep the atoms even of solids into every style of arrangement and polarization, and consequently must have a tremendous momentum. The etherio-atomic law demonstrates this point in a multitude of ways. Dr. William B. Carpenter, who seems to be but little acquainted with the fine forces, has written an article in the "Nineteenth Century," in which he takes the most difficult methods of explaining away the power of radiation to produce electricity and mechanical force as in the radiometer. "There is no reason whatever," he says, "for attributing to radiation any other power of exciting an electric current than that which it exerts mediately through its power of heating the thermopile." Even if this assertion should prove true, how can sunlight heat the thermopile, or anything else, except by the impact and momentum of its rays upon it, especially as it is admitted that radiating light has no perceptible heat of itself, excepting as it strikes something?

XIII.—Polar Cohesion of Atoms.

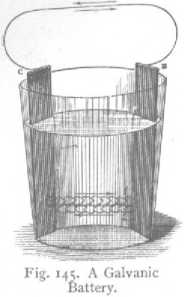

I think the ground is now sufficiently clear for an understanding of the methods by which atoms become polarized and combine into solids and other substances.

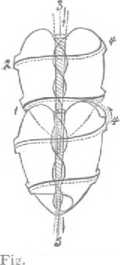

| 137. Polarized Atoms. |

Fig. 137 represents two atoms polarized and joined at 1, the upper atom sinking into the lower as far as the positive thermo spirals, which thus regulate the distance. The dotted lines represent the ethers which flow axially from 3 to 5, and thermally around the atoms in the other direction; 4, 4 shows how the ethers are drawn on from one atom to another by the eddy-like forces of the spirals and spirillae of the same grade with which they come in contact. The ligo of the upper atom glides into the ligo of the lower, and the two thus become riveted into one, and held doubly tight by the spiral sweep of the ligo-ether. The artist has doubtless represented the upper ligo as being inserted too far in the lower ligo, as the axial spirals which encircle the upper might interfere somewhat, unless they are exceedingly elastic. But how do the atoms thus arrange themselves in this orderly manner? Why do not the wrong ends come together? Not only does the vortical and ligo suction of the lower atom draw the second, but the torrent or axial current above drives the second against the lower atom and holds them together. They could not possibly be joined wrong end first, as the currents would then drive in opposite directions, and repulsion would occur. They can no more avoid this arrangement under the play of ethereal forces than a stick of wood on the brink of a maelstrom can avoid being swept in. The positive end of the line is at 5, the negative end at 3.

XIV. Lateral Cohesion.

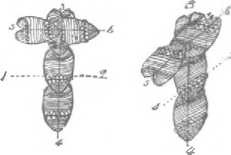

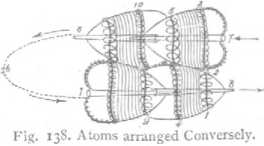

1. Having explained the mystery of polar cohesion, let us see how atoms can cohere laterally. Fig. 138 presents two lines of

polarized atoms drawn with a single thermo spiral and its first spirilla. The lines are placed conversely so that a positive spirilla of one atom occurs by the side of a negative spirilla of another. If they were placed so that the eddies of two

positive spirillae should come together, they would repel each other; but a powerful eddy placed near a feeble one would overcome it and draw it toward itself. Thus the positive spirilla 1, outdraws the negative spirilla 3 at the point 2, and so links that portion of the upper atom to the lower, while the positive spirilla 5 outdraws the negative spirilla 4, and thus holds that portion of the lower atom as firmly as the lower atom held the upper in the other case. The other atoms work in the same way.

2. Thus we see that heat action, which is generally so expansive and disintegrating, may become an element of cohesion, though a much feebler one than cold exerted through the ligo, and axes of atoms in polar cohesion. This will explain why wood, stratified rock, etc., will split more easily in one direction than another. The polar cohesion is in the direction of the fibres, grains of wood, etc., while the lateral cohesion is at right angles to this. The curved line, showing how ethers may pass out of the torrent end of one line of atoms and be drawn into the vortex end of another line, will give a hint of how magnetic curves are formed, although it is incorrect to represent it as passing out and into contiguous lines or out and into the same layer of atoms.

3. The cut will show how atoms can communicate their impulses laterally, as from 1 to 3, as well as longitudinally from 7 to 8. The lateral movement of light may be understood by studying it, as it can never be understood otherwise.

XV. The Unity of Atoms.

Judging by all other works of nature, atoms must be united by bonds of unity through all their parts, so that all spirals must be connected more or less with all other spirals by small pillars or tubes. These may be called atomic tendrils. The 3rd spirilla imparts action to the 2d, the 2d to the 1st, and the 1st to the parent spiral itself, while each spiral is so connected with its brother spirals as to act and react upon them. Even the thermo spirals are doubtless connected with the intra-spirals, as well as with each other, by delicate tubes which are so arranged as not to impede the passage of ethers. In this way atoms are doubly armed against stagnation and death, for if only a single ether should be moving through the minutest spirilla, it would impart more or less of its vitalizing power to the whole atom.

XVI. —Converse Layers of Atoms

Are such as are represented in the cut, fig. 138, with the lines running in parallel but alternately in opposite directions. The next layer placed upon this would exactly reverse the order, and be the same as this turned over, so that the upper atoms would come on the lower and the lower on the upper. This must be the arrangement of the cosmic ether by means of which it is enabled to carry both cold and warm forces to and from the sun and other orbs. It is probably also the most common arrangement of ordinary matter.

XVII. —Transverse Layers of Atoms

Are those which cross each other at right angles, or nearly so, and must bind the particles into a greater hardness or toughness than they would otherwise have, as they are polarized longitude-nally and laterally. Steel must be composed of transverse layers just as iron is doubtless composed of converse ones mainly. I will mention here simply two proofs of this, 1st, steel or car-buretted iron is harder than ordinary iron; 2d, magnets must necessarily have transverse layers of atoms as can be demonstrated by this atomic law, as well as otherwise. Steel when once magnetized remains a permanent magnet because of its transverse polarizations, while the layers of iron arc held transversely only when under the electric or magnetic current, consequently its magnetism ceases when the current is withdrawn. See XXX of this chapter.

XVIII. —Laws of Atomic Combination.

1. Atoms must combine to a considerable extent according to the general law of their spirals. Two distinctive styles of atoms seem to be clearly demonstrable in different substances, in one of which the spirals move around almost perpendicular to

| Fig. 140. Transverse Diagonals,Fig. I3<).Transverse Lines. |

the direction of the atom, as in fig. 139, while in the other, their movement is more diagonal as in fig. 140. The former would tend to make the atoms broader and capable of more specific heat, while the latter would extend them into a longer and narrower form, with the external spirals more drawn

out, somewhat as they are in the axial or electrical portion of the atom. The one would doubtless find its type in steel, the other in bismuth or antimony, the specific heat of which is exceedingly small.

2. Figures 139, and 140 will show just why certain substances will have tranverse polarizations, in which the layers of atoms cross each other very nearly at right angles, while others will have transverse diagonals, for the following reasons:—The spirals in 139 running in the direction of 1, 2, form little whirlwinds of force in that direction which, striking a contiguous line of atoms, must tend to wheel it around accordingly and hold it there, especially under excitement, as in 5, 6, while in fig. 140, the lines of force being diagonal, must sweep the atoms around until they become diagonally transverse, as in 5, 6. In most cases, however, it is probable that the line 6, 5, should be reversed with the vortex end at 6 instead of 5, in which case we could easily see how such a phenomenon as double refraction might occur as in Iceland spar, a part of the light striking at 3 and moving on to 4, and another part striking at 6 and moving on to 5.

3. It is evident that when any substance is aroused to extraaction by friction or by passing an electrical current through it, a part of the lines will be thrown into a transverse arrangement, or at least into transverse diagonals, according to whether the spirals pass around the atoms, as in fig. 139, or obliquely, as in fig. 140. What proof have we that this is so? We know that if we rub any object briskly, and hold it near a hair or some other light object, it will attract it. The fact of this attraction shows that there are eddies of etherial force which sweep around in and out of the object frictionized, and draw other objects towards itself. But what has this to do with showing that excited objects have their atomic lines arranged transversely? my reader may say. Just this; if the lines should all run in the same direction, there would be no counter-currents to deflect them so that the neighboring vortexes could draw them in and thus establish a circuit of forces which, like a miniature whirlwind, is attractive to everything around. Thus a piece of iron in its ordinary condition will attract nothing, but pass a current of electricity through it and it immediately becomes magnetic and highly attractive, and this attraction is caused by circuits of force as shown by iron filings which may be placed above it on a piece of paper. (See. fig. 23.) Glass must have its atomic lines polarized in various directions, or it would not be transparent in all these directions, for which reason it is highly attractive when excited, and for which reason, also, glass and other irregularly polarized objects are called non-conductors of electricity as the transverse lines obstruct the electrical ethers. Transverse diagonals, if not arranged somewhat amorphously, must be less obstructive and consequently better conductors of both heat and electricity than transverse lines in which the more perpendicular spirals rule, as in fig. 139. Silver, copper, etc., which are such fine conductors, may be presumed to be more diagonally arranged than steel, which is a poor conductor, comparatively. Good conduction also requires continuous lines of polarity, and all amorphous bodies must necessarily be poor conductors, as well as all bodies which have polarizations in too many directions, like gutta percha, leather, etc. That these last bodies must be polarized in various directions is evident from their toughness in all directions, the greatest cohesion, as we have seen, being in the line of polarity.

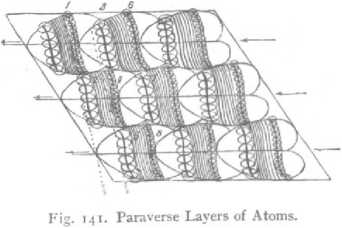

XIX. Paraverse Layers of Atoms.

Are those in which the lines are all turned in the same direction, (See fig. 141), the positive spirillae of one line being arranged

against the negative spirillae of the contiguous line. This should give seemingly a lateral cohesion about the same as that in converse lines, though somewhat less perhaps from the less perfect union of graded spirillae. It throws the second range of atoms a little farther along than the first, the third one still farther on, etc., resulting in diagonally formed and rhomboidal crystallizations, as in bismuth, antimony, quartz, ice, etc. It is probable that this paraverse arrangement of atoms comes from diagonal spirals. It will be seen in the cut how the large, active sub-coils of one atom come opposite to the feebler ones of another so as to promote attrac-

tion. Thus the positive spirilla 7 binds the negative spirilla 6 and 8 to it, 2 draws 1, 5 draws 4, etc.

XX. Crystalloid and Amorphous Bodies.

Crystalloid and other regulary formed or morphous bodies are such as grow into some definite forms on account of a general and regular polarization of their atoms. They are capable of strong chemical effects, and examples of them may be seen in crystallizations, stratified rocks, grained woods, etc. Amorphous Bodies, or literally those without form, are deficient in continuous polarities and orderly arrangement of molecules. Clumps of earth, many ores in a crude state, pulverized substances, snow, etc., are amorphous. When the ores are worked up into bars of metal, they generally become more or less crystalloid. No forms whatever are entirely destitute of polar arrangement, but amorphous bodies have but short or irregular lines of force, and consequently are negative and lacking in chemical effect.

XXI. Heat and Cold.

1. Heat expands, individualizes, works on the centrifugal law, and in excess tends to disorganize and tear into pieces; Cold contracts, polarizes, organizes, crystallizes, works on the centripetal law, and in excess tends to lifelessness and congelation.

2. The Law of Motion for heat is the spiral with its eddies of force passing around the outside of atoms; that for cold is the same combination of eddies narrowed down to a vortex which passes in the opposite direction through the axes of atoms, and becomes swifter, narrower, and straighter as it proceeds.

3. The greatest Heat Lines are in the greatest curves—the greatest Cold Forces approximate more and more the straight line.

4. Heat produces its sting by laying on countless millions of lashes every second, and cold, by piercing with countless gimlets on the boring process.

5. There are various grades of heat and cold, the coarser grades consisting of the coarser ethers passing through the coarser spi-rillae. These in excess are more painful and hurtful to the human system, while the finer grades, being connected with the finer spirals, are more penetrating and soft in their influence. (See Chap. First, XV.) We may be pierced by a razor, and it will hurt us far less than will so coarse an instrument as a hoe; a current of electricity may penetrate entirely through a portion of our bodies, and make but a gentle shock from its fineness, while currents of human magnetism, being still more exquisite, may at times permeate the whole system without our consciousness. This will explain the effect of different grades of fineness of heat and cold, and will also show why sun-light is less hurtful to the eyes than the coarser gas-light, which has more of the yellow and red principle, and why the color-electricities of blue and violet, for instance, are so much softer than the electricity of the battery.

6. It may be well to remark that all the finer grades of cold are simply grades of electricity, as will be seen hereafter.

7.1 will merely hint here at the fact that the heat and cold principles in atoms form a chemical affinity for each other, which explains why it is that the greatest heat is developed by combining cold and electrical elements with those which are warm, as the blue with red light, or the electrical principle of oxygen with the thermal principle of potassium, by the union of which a flame is kindled. (See Chromo Chemistry.)

XXII. Atomic Divisions.

1. Before we can understand the philosophy of force we must thoroughly understand the construction of atoms. If any one should remark that no human eye has ever seen an atom, and consequently it cannot be described, I would remark, 1st, that human reason, aided by scientific discovery, can penetrate far beyond telescopes and microscopes; 2dly, I conclude that this atomic theory is fundamentally correct, because it explains multitudes of mysteries not before understood, and harmonizes with or corrects all scientific facts or hypotheses to which I have applied it. If I should apply a key to a hundred doors in some temple, and it should unlock them all, I should say it was the correct key; 3dly, by understanding law we may at times discover a fact or truth by means of reason sooner than we would by outward perceptions without a knowledge of law, just as LeVerrier discovered where the planet Neptune must be from his knowledge of mathematics, before it was discovered by the telescope. I admit that we must test theories by facts and facts by theories, a rule which may be observed with reference even to atoms, and which I have ever aimed to observe.

2. I must again ask the reader to take some of my statements at present on trust or from their apparent reasonableness, promising hereafter in this work, and still further, in a succeeding one, to give facts and reasons. If so much discussion of the subject of atoms is considered dry reading, it should be remembered that we shall be but charlatans in science until we can reach basic principles.

3. We have, then, the atom with its wonderful diversity of powers, including thermal spirals and spirillae, axial spirals and spirillae, and the ligo tube, with all the internal and external ethers. I have called the form of the atom an ovoid, but this ovoid is evidently more or less oblate or flattened, 1st, because it would combine more systematically to form layers of matter, and 2dly, because it would readily assume such a form, as the axial spirals, emerging near the small positive end with great velocity of vibratory force, would naturally be swept too far one side to make a complete circular spiral, and so it would assume more of an oval spiral, exactly in harmony with the motion of planets around the sun.

4. As to the extra or thermo spirals, the following are among the arguments in proof that the foregoing conception is founded on nature; 1st, it is an important dual division of forces in harmony with analogies in general; 2dly, atoms can be inserted into each other by an exact system in the ordinary polar cohesion and by another exact system in chemical combinations in case certain thermo spirals project beyond the rest, and thus form regular barriers; 3dly, frictional electricity, especially, is confined to the surface of bodies, and is aroused by external friction or pressure which goes to show that some part of their spirals is external; 4thly,the fact that frictional electricity is swifter than other grades could be accounted for by supposing its spirals to be the most interior in the axis of atoms where the pathway is shortest and nearest straight. But if its axial spirals are most interior, their thermal portions would naturally be the most exterior; 5thly Magneto-electricity and magnetism can penetrate considerably below the surface of bodies, which could not be if any part of the spirals concerned were external, as their action would then be smothered before they had penetrated far within. This shows the necessity of intra-spirals. 6thly, the fact that the electrical colors can penetrate deeply within substances, as in the case of seeds which are reached and germinated by them to a considerable depth below the surface of the soil, shows that no part of their spirals is external, consequently colors must require intraspirals.

5. That there are seven intra spirals in ordinary transparent bodies, six of which constitute the principle of the thermal colors when moving thermally, and that all seven of the same spirals, when moving axially, constitute the principle of the electrical colors, will be more and more evident hereafter. That there are seven intra-spirals of somewhat coarser grade in iron, copper and other opaque bodies, devoted to the manifestation of different grades of heat and electricity, will be shown in this chapter, XXXIII., 2.

XXIII. Cohesion.

1. We have already seen how the Ligo rivets the atoms together until they become masses of solid substance, such as metals, rocks, woods, bones, muscles, etc. The suction caused by the ligo ether, together with the firmness of its parts, must cause the principal cohesion, although the other ethers assist to some extent.

2. In such a metal as mercury and in the liquids and gases, the ligo is probably wholly wanting, excepting as some foreign substance may exist in their midst.

3. In case of intense cold the vortical and electrical forces become so swift as to sweep the atoms together into a congealed or solid mass without the aid of the ligo, except as foreign particles may intervene. It should be remembered that the tendency of cold is not only to diminish the size of all atoms, but to thicken or harden all masses of atoms. The fact that water, and melted iron, bismuth, zinc and antimony, become somewhat increased in bulk on becoming hardened by cold, does not invalidate the rule, but shows how the process of crystallization can pile some polarized lines upon others in a way to enlarge their size as a mass.

4. When the heat becomes very great the spirals of atoms expand to such an extent and become so furious in their centrifugal action as to throw even the particles of iron and other metals asunder in a melted condition, in spite of the ligo, and when much greater still, the atoms become so detached as to be wafted off into the air on the swift currents of ether, in the form of vapor. The tendency of heat is to soften and disintegrate. If bodies like moist clay become hardened by heat, it is because it evaporates the water and leaves only the atoms which possess the ligo. The small amount of cohesion that exists between the atoms of liquids, gases, and ethers, comes doubtless from the flow of electrical forces through their axes.

XXIV. Different Kinds of Electricity.

My researches in connection with my studies of atomic law have convinced me of the existence of six or more distinct grades of electricity, besides some minor divisions, namely, Frictional Electricity, Chemico Electricity, Galvano Electricity, Magneto Electricity, Chroma Electricity, and Psycho Electricity. The swiftest of these, so far as known, is the Frictional, although Chromo-Electricity is much softer and more penetrating. A brief account of these will be in place here. Psycho-Electricity will be explained under the chapter on Chromo-Mentalism.

XXV. Frictional Electricity

Is sometimes improperly called Static (standing or stationary), as there is no such thing as any electricity which is not in rapid motion. According to Wheatstone this style of electricity moves at the rate of 288,000 miles a second. For the reason of its swiftness and intense action see XI. 5, of this chapter. Its element is electro-ether while its principle consists of the axial portion of the thermo-spirals, for the character of which see fig. 135. Being extra spirals in their thermal portion, it will readily be seen why all friction, rubbing, and pressure, will arouse them into action, produce heat as well as electricity. It may be asked why is not frictional electricity, as developed by the electric machine, used for healing purposes? Because it moves almost entirely on the surface of the skin where the nerves of sensation are most active, consequently its effect is exciting rather than soothing or healing. Frictional electricity, as aroused by the hand moving over the surface, is generally very vitalizing and soothing as it is softened down by the finer vital electricities. Magneto and chromo electricity are finer than the frictional, penetrate more deeply from being connected with intra spirals, and are better for therapeutical purposes. What is called thermo-electricity is often mere frictional electricity, aroused by direct heat in connection with the thermo spirals.

XXVI. Chemico Electricity

Seems to be caused by a somewhat coarse ether moving in connection with the axial portion of the coarsest of the intraspirals (see fig. 22), corresponding probably to the spiral for blue green only coarser, ft is doubtless the electricity which is generally called negative in its nature, except in galvanism, although the substances which constitute its most natural abiding place from having the right sized spirals, are improperly called electro positive, such as potassium, sodium, the metals, etc., while other substances in which frictional, galvano and magneto electricity most naturally dwell are called electro-negatives, such as oxygen, sulphur, etc., although these kinds of electricity are strong positive grades as compared with chemico-electricity. To avoid confusion, however, I shall sometimes adopt the terms as scientists have generally established them, begging the reader to remember that what are called electro-positives are substances which are really the most feebly electrical, while those which are called electro-negatives are those which are really the most electropositive, or, in other words, which are the most strongly electrical. The scientists have fallen into this error from supposing that electricity is a mere dynamical force dwelling entirely within the atoms of a substance, and as dissimilar electricities attract each other, a substance was supposed to be negative in case a positive electricity was evolved from it and vice versa. Under the caption of Galvanism it will be shown how chemico electricity is evolved in connection with the zinc of the battery and moves through the sulphuric or nitric acid to the plate of copper or platinum, while a finer grade of electricity, the galvanic, passes from these latter metals to the zinc. Three things are especially evident with respect to chemico-electricity,—1st, its movement is always attended with more or less heat as well as cold; 2dly, other things being equal, it is the feeblest of all grades of electricity and the least electrical in its nature, for which reason it is sometimes called negative by electricians; 3dly, in galvanism it moves through alternate lines of converse atoms in exactly the opposite direction from galvanic and magnetic electricity. Its movement is attended with heat and a feeble grade of electricity, because, being the last spiral to enter the axis of the atom (see fig. 135), it must necessarily encircle all the rest and have less of that swift narrow and pointed style which constitutes cold and electricity. The causes of its moving in opposite directions will be given under the head of Galvanism, XXXIV.

XXVII. —Galvano-Electricity

Is a grade finer than the chemico, and answers to the axial spirals which correspond to the electro-lumino spirals for the blue, including also indigo-blue and probably indigo, though coarser than these. It is the finer positive electricity which moves in the galvanic circuit from the copper to the zinc, etc., and doubtless exists in many so-called electro-negative substances. How do we know that galvano-electricity is not as fine a grade as that of the blue color? Because if it were it would give out a blue appearance, and moreover its effects are less soft and penetrating than those of blue sunlight. See Galvanism, XXXIV.

XXVIII. —Magneto-Electricity.

A Grade finer than the galvano, and made in connection with spirals that correspond with the electro-lumino-spirals for the violet, including violet-indigo, violet and dark violet. The finest induced currents of the battery, sometimes called Faradaic, from Faraday, consist of magneto electricity. The positive pole of the magnet gets its power from magneto electricity bent into curves, while the negative or south pole is presumably charged with the chemico-grade. See Magnetism (XXX.) Although the magneto grade is coarser than the color electricities, yet, under the force of the magnet, it is readily driven through glass whose spirals form a natural pathway of light and color. This may be proved by placing iron filings on a pane of glass and holding a magnet below it, in which case the filings will be thrown upward and also into a great number of lateral curves on both sides.

XXIX.—Chromo-Electricity.

We come at last to a grade of electricity whose ethers and spirals are fine enough to appeal to the eye in the form of the electrical colors, such as blue, violet, etc., already mentioned. Although the scientific world has not yet learned that these colors constitute one grade of electricity, yet they have discovered many facts that bear in that direction. I will mention some points in proof:—

1. Electricity, as I have already shown, consists of the cold contracting principle. The violet end of the color scale is known to consist of cold colors, just as the red end is warm, as shown by the thermometer and thermo pile.

2. Morichini, Carpa, Ridolfi, and Mrs. Somerville state that, by exposing common steel needles to the violet rays of a spectrum, or by covering one-half of them with blue glass, they become magnetic. Атрёге has shown that magnetism is identical with electricity, and it will be shown hereafter in this work that magnetism consists of electricity thrown into curves by passing in transverse lines. The persons who deny the electrical character of the violet and blue rays present insufficient facts, although the grade of electricity is finer than that which usually influences the galvanometer, or perhaps even the magnet.

3. Zantedeschi exposed a magnet, which would carry 15 ounces, to the sun 3 days, and increased its power two and a half times. Barlocci found that a magnet which would lift one pound, would lift nearly two pounds after exposing to strong sunlight 24 hours. No one will pretend that the red or other thermal colors could have done this, while the facts of the last paragraph show that the violet end of the scale is quite competent to it. The reader may wonder how sunlight can arouse magnetism if, as I have shown, the magnetic ethers are somewhat coarser than chromo-electricity. I shall show hereafter under the head of Fluorescence (XXXIII), and elsewhere, that under stimulus, coarse ethers can sometimes be forced through spirals which are naturally too fine for them, and fine ethers through spirals which are naturally too coarse for them. Although chromo-electricity may stimulate, and to some extent pass through the atomic spirals of a magnet, this stimulus evidently tends to draw in from the atmosphere magneto-electricity, especially in cold weather, from the fact that if the former electricity were sufficiently abundant, the magnet itself would be bathed in blue and violet colors.

4. Electricity being the principal cause of phosphorescence, and these colors having the same power, tends to prove their similarity of character. "Beccaria examined the solar phosphori," says Prof. Hunt, "and ascertained that the violet ray was the most energetic, and the red ray the least so, in exciting phosphorescence in certain bodies. M. Biot and the elder Becquerel have proved that the slightest electrical disturbance is sufficient to produce these phosphorescent effects. May we not then regard the action of the most refrangible rays, namely, the violet, as analagous to that of electrical disturbance? May not electricity itself be but a development of this mysterious solar emanation?" To this question, aided by our knowledge of atoms, we may answer no, so far as ordinary electricity is concerned, as ordinary electricity and magnetism are aroused only indirectly by the solar rays.

5. Electricity is the principle of cold, but, by means of chemical action with thermal substances, can develop the greatest heat known; in the same way blue, indigo and violet constitute the cold end of the spectrum, and yet by means of chemical combination with thermal colors can develop greater heat than could be done with the red color alone. I will cite one example merely. General Pleasanton, of Philadelphia, by putting blue glass in among the panes of clear glass so as to bring blue and white light together, caused the thermometer in his grapery to rise to 110°, while on the outside the temperature was only 35° F., or a little above the freezing point. The General supposed that this effect occurred partly by gaining some electrical force from transmission through the glass, but we shall see under Chromo-Chemistry that the blue rays develop this great heat by combining chemically with the thermal rays of the sunlight. Like other styles of electricity the blue and violet colors can develop no heat, excepting in chemical affinity with warm substances, or when bent into magnetic curves.

6. The odylic colors, explained in the chapter on Chromo Dynamics, and developing the finer potencies of things, prove the electrical nature of blue, violet, etc.

7. It will be fully shown hereafter in this work, that there can be no possible style of chemical affinity without combining some style of electricity with the principle of thermism in atoms. If it should be proved that all shades and hues of blue, indigo and violet fill the office of electricity in chemical combinations, would it not be absurd to say they are not electrical? How fully this can be proved will be seen hereafter.

8. Thus do we have the most overwhelming proofs from the construction of atoms, and from actual experiment, of the electrical nature of these colors, including blue-green, blue, indigo-blue, indigo, violet-indigo, violet and dark violet.

XXX.—Magnetism.

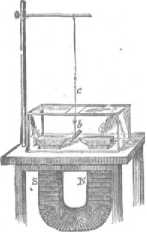

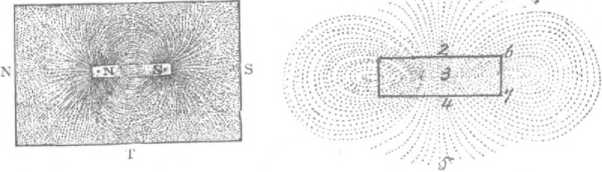

1. Having attained to some conception of electricity as a principle and as an element, and the law of its movement through atoms, it would be well to inquire how it is modified to constitute magnetism. We have already seen that the reason why steel constitutes a permanent magnet when once charged with the proper electricities is, that its atoms must be arranged in transverse layers. This is shown by a bar magnet placed under a piece of card-board or glass upon which iron filings are lying, as in fig. 143. These filings will be drawn into concentric curves each side of the magnet, currents of ether sweeping in connected circuits around, through and on both sides of the magnet, sometimes making the filings project a half an inch above the glass, while through the centre in the direction of N. and S. they he in straight lines, ft is easy to see how transverse lines of force, caused by transverse atoms passing at right angles, could deflect each other from a straight fine, and being once deflected they could be drawn into a neighboring vortex of a line of atoms in the magnet where, after passing through, they would be deflected again and perhaps return into the same old channels of the magnet to continue their endless circuits.

2. The straight lines through the centre show that some lines of force are constantly gliding through the magnet lengthwise, having its influx at one end, its efflux at the other. Experiments, especially with the odic lights and colors, seem to prove that these lines of force, sweeping in one direction, consist of magnetoelectricity which passes in at the south or negative pole and

9